States May Be Interested in Value-Based Payments, but Commercial Insurers Are Not

States May Be Interested in Value-Based Payments, but Commercial Insurers Are Not

CMS has issued the fourth of five planned annual reports on its Medicaid State Innovation Models (SIM) Initiative. Under the SIM initiative, six “test states” – Arkansas, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Oregon, and Vermont – have been awarded funds and are using policy levers to facilitate the creation or spread of innovative models and integrating population health and broader stakeholder perspectives into health care delivery and payment redesign models. The latest report describes the experiences of providers, health systems, consumers, payers, and state officials during the final full implementation year.

The evaluation, conducted by RTI International, working with The Urban Institute, National Academy for State Health Policy, and The Henne Group, found all six states have introduced value-based payment models (VBP models) in their Medicaid programs and are offering technical assistance to providers, social service and community-based organizations, and others to implement new delivery system models. States are also offering services, such as health IT and data analytic investment, that “enable or improve model effectiveness,” according to the Year 4 Annual Report.

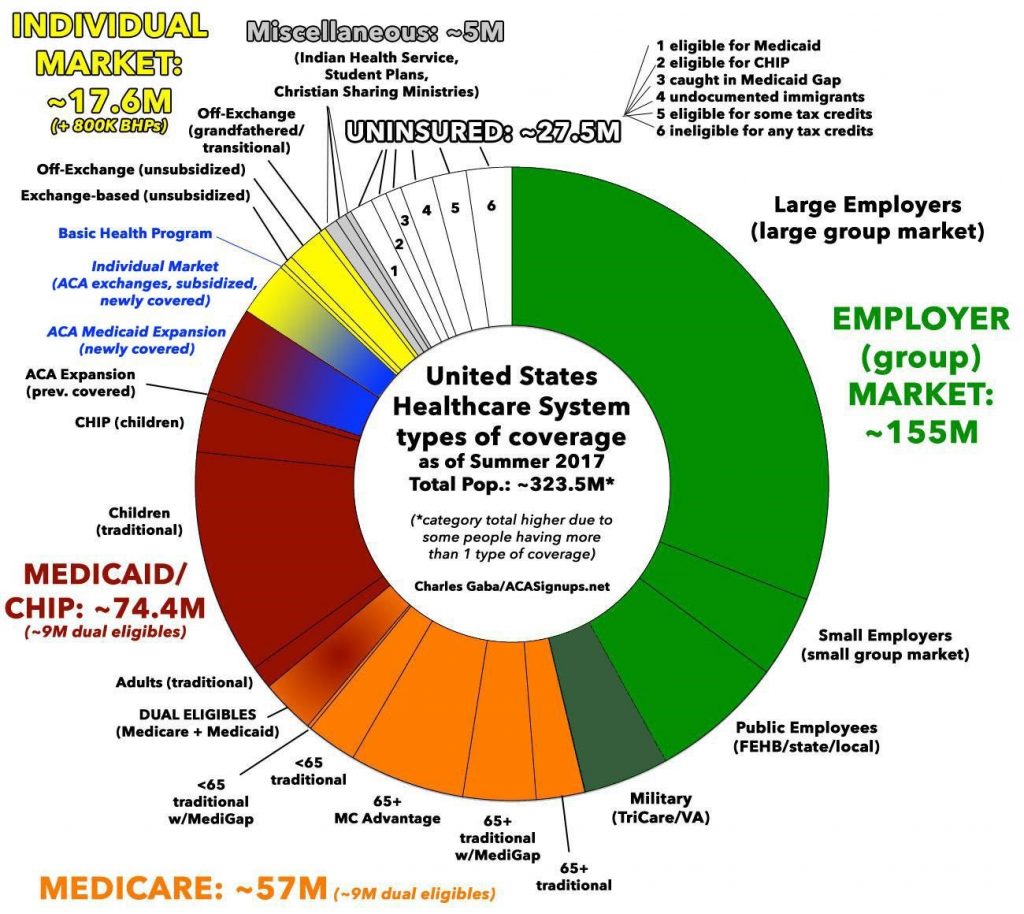

However, the evaluation found “limited interest” among private payers and insurers in aligning their existing VBP models with state models. “All states struggled with effective engagement of private payers and insurers to expand VBP models beyond existing efforts and to achieve alignment across multiple payers,” the report finds. “Although private payers and insurers were willing to discuss the states’ conceptualization of VBP models, most did not make changes to the VBP models they offered to providers.”

As a result of limited interest among commercial payers, “states ultimately focused on Medicaid or state employee health plans over which they had control.”

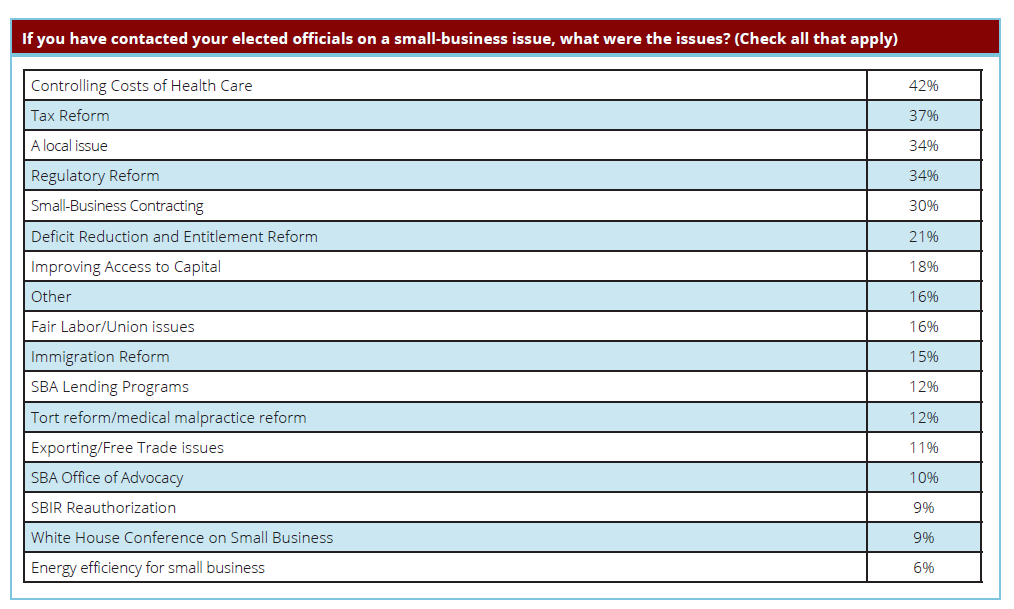

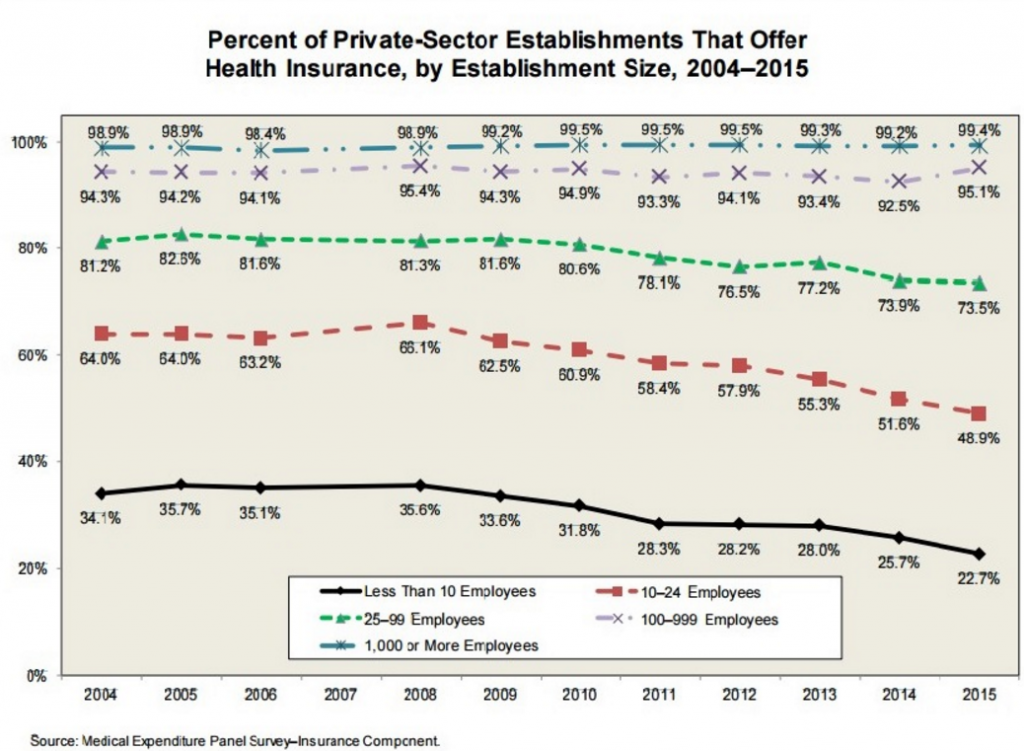

There are several factors contributing to this lack of multi-payer alignment around common payment models, including a difference in business goals between Medicaid and commercial payers. Commercial payers in Maine, for example, reported issues related to value-based insurance design and multi-payer measure alignment; this was due to “insufficient engagement with payers” when the SIM goals were established, the report says. In addition, commercial payers in Maine are reluctant to change the design of their insurance products “in response to a single state’s recommendations,” and there is a “preference for making product design changes in response to their clients’ needs.”

If you are a business, your client’s needs come first. If a state becomes a client of an insurer, perhaps this VBP model alignment problem would be easier to solve. But other state’s experiences would indicate that is unlikely.

The RTI evaluation identified several other factors contributing to the lack of payer alignment in payment models including: the proprietary nature of information (e.g., commercial payers in Minnesota preferred not to share details on quality and utilization measures and performance reports for providers, which “limited the type of dialogue necessary to advance multi-payer payment reform”) and competitive concerns (e.g., payers that have invested in changes in payment reforms are “concerned that the returns on those investments are accruing to other parties”).

Many of these concerns are age-old problems; in the policy world, we encounter these types of issues frequently: (1) the complaint that “you didn’t engage us from the beginning;” (2) the fact that health care delivery is competitive in a capitalist market; and (3) the free rider problem.

We could add two more issues or concerns to the list above: (4) “You don’t understand clinical issues” (e.g., physicians in Arkansas felt that “state decision-makers were too far removed from daily clinical practice to understand what would work effectively”) and (5) We would have to create multiple products – e.g., products tailored to the needs of the Medicaid population vs. commercial population.

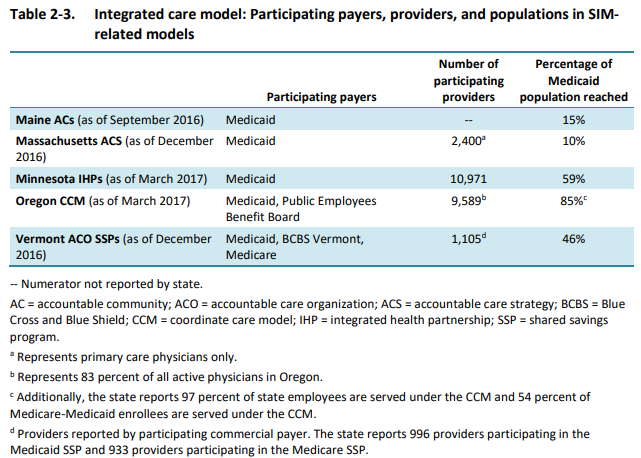

In the six test states, participation by health care practitioners in innovative models varies wildly. For example, in testing an integrated care model, the number of participating providers varied such that in Massachusetts, 10% of the Medicaid population was reached, while in Oregon, the comparable figure was 85%, as noted in the chart below (from the evaluation report):

For tests of the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) or health home model in these six states, 17% of the Medicaid population was reached in Maine, compared with 70% in Vermont and 75% in Oregon.

Engaging private payers in innovative payment models is important for health care system transformation. Given that some payers in these six test states were reluctant to change the design of their insurance products in response to a single state’s recommendations, states might consider combining forces for the purposes of designing more responsive VBP models. Another alternative is to ask insurers, along with representatives from other health care entities, consumer groups and employers to participate in system design change from the beginning of the process. VBP may lead to health cost reductions if implemented widely and well, but such achievements will be nearly impossible if entities that control so much of a population’s health care coverage choices are not involved.