Same health care, different setting, but much higher costs

Same health care, different setting, but much higher costs

There is so much health care news happening right now, you may not have seen this, but different services cost different amounts, depending on where they were delivered. While this concept isn’t necessarily news to health care policy types, this latest data set and accompanying graphics make the issue clearer than ever and beg for a policy fix.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) finalized the Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment and Ambulatory Surgical Center Payment Systems and Quality Reporting Programs Rule November 21, 2018, implementing site neutral payments for hospital outpatient clinic visits. The policy essentially reduces payments for services provided in outpatient settings to the same level as the payment made for the same service in a physician’s office.

However, the policy change applies only to Medicare, which covers less than 20% of the U.S. population. The commercially insured, for example, via employer-sponsored insurance and the individual and small group market, account for 56% of the population (see Charles Gaba, The Psychedelic Donut: Types of Coverage in the U.S.).

Wouldn’t a similar policy for people who receive health insurance outside of Medicare be a way to reduce costs?

Outpatient setting is always more expensive…

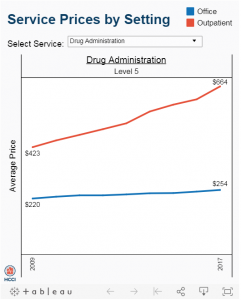

The Health Care Cost Institute compared a common set of services performed in physician’s offices and outpatient hospital settings and found “for this set of services, the average price was always higher in an outpatient setting than an office setting.”

Services that saw a significant change when provided in an office vs. an outpatient setting varied by service. Some of the bigger changes were for ultrasounds, upper airway endoscopies, and drug administration. For example, “in 2017, 45.9% of level 5 drug administration visits occurred in outpatient settings, compared to 23.4% in 2009.”

Not only did prices increase over time for both settings, the site differential for some of the visits was stunning.

We took the HCCI info and added a calculation of our own for a few of the visit types to show the percentage difference between the price of a visit in the office setting vs. outpatient setting, as shown in the table below.

It is also something that should be made transparent to patients. As mentioned in a recent , health care costs are rising and people are struggling to afford those costs. States are passing transparency bills left and right (hospital transparency, drug price transparency), even though it is unclear how “transparency” actually lowers costs. However, implementing site neutral payments for all payers (not just Medicare) is a more obvious, and more immediate, improvement to rising health care costs.