Is this the year we finally talk about all health care costs?

Is this the year we finally talk about all health care costs?

While patients, families and employers have been talking about rising (and in many cases, unmanageable) health care costs for years, it appears researchers finally may be getting on board with the issue as well.

Three notable reports came out in the past few weeks comparing what the U.S. spends on health care to other countries.

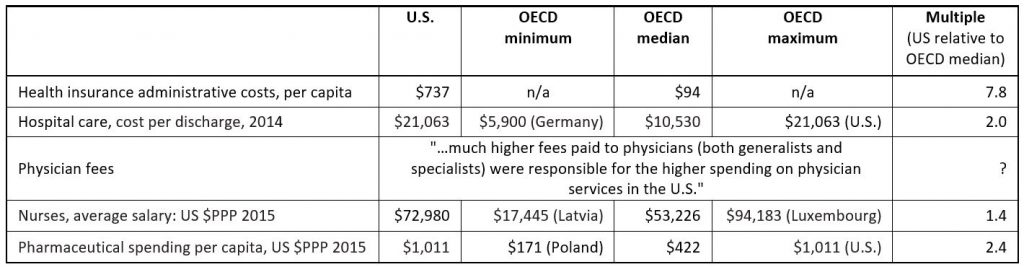

The U.S. System Costs More to Administer than Other Countries

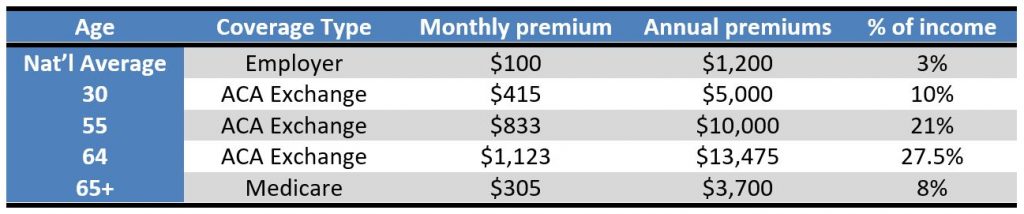

The Annals of Internal Medicine published a study on January 7, putting new numbers to an old question. How much does the U.S. spend on the administration of health care? About four times more than Canada spends, evidently. Administering care is much cheaper in Canada, for example, because there are standardized forms and processes for providers, facilities, and families to use to access and pay for care. The study authors estimate $600 billion a year is spent in the U.S. on administrative bureaucracy instead of clinical care. On a per person basis, this amounts to $844 spent per person for health insurance plan overhead in the U.S., versus $146 per person in Canada.

The U.S. System Pays Physicians More than Other Countries Do

It’s not just health plan administrative costs that drives U.S. spending higher, though as we have written , streamlining forms and processes seems like an obvious place to start cutting costs. The U.S. also pays physicians more than other countries do. Anne Case and Angus Deaton – the economists who called attention to the rising number of “deaths of despair” in 2015 (and won a Nobel prize for their work that year) made headlines this week at the annual American Economic Association’s annual meeting when they said physicians are driving U.S. health care costs:

“We have half as many physicians per head as most European countries, yet they get paid two times as much, on average…” says Deaton. “Physicians are a giant rent-seeking conspiracy that’s taking money away from the rest of us, and yet everybody loves physicians. You can’t touch them.” (source: Washington Post).

Is this a Good Thing or a Bad Thing? (I ask in jest…)

Maybe the Internet coordinated these news reports, but the same day the Case/Deaton comments came out, several news outlets reported: Health care positions top 2020 list of best (paying) jobs! Indeed, 12 of the top 20 best paying jobs for 2020 are in health care. Here is the list from US News and World Report:

Best-Paying Jobs

- Anesthesiologist

- Surgeon

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon

- Obstetrician and Gynecologist

- Orthodontist

- Psychiatrist

- Physician

- Prosthodontist

- Pediatrician

- Dentist

- Nurse Anesthetist

- Petroleum Engineer

- IT Manager

- Podiatrist

- Marketing Manager

- Financial Manager

- Pilot

- Lawyer

- Sales Manager

- Business Operations Manager

It’s good to see more attention being paid to costs, and it’s especially good to see research and data behind the alarming stories. We all know that health care costs are going up but if we really want to do something about it, we have to look at ALL health care costs. This kind of data is the first step toward policy making; let’s see what happens next.