“Medicare-for-All” Understood as Lower Premiums for Me?

“Medicare-for-All” Understood as Lower Premiums for Me?

Proposals for Medicare-for-All, or more accurately, universal health coverage, are being introduced by both Congress and state legislatures at a rapid pace (see this useful interactive tool, The Many Varieties of Universal Coverage from The Commonwealth Fund). While policy types argue over how such a plan would be funded and how to set reimbursement rates for providers, and Wall Street frets about what single payer health coverage would do to health insurance companies, state legislators and regular people seem to have a different perspective. In my many conversations with people across the country about the idea of “Medicare-for-All,” I have found it striking how often people say they favor such an approach because they want lower health insurance premiums.

I think we may have a language problem. When health policy people hear “Medicare-for-All”, they think “change the health care delivery and insurance infrastructure from employer contributions to taxpayer contributions,” but maybe when regular people say “Medicare-for-All”, they mean “please find a way to lower my premiums”. The Kaiser Family Foundation Health Tracking Poll conducted in early January hints at the importance of lower premiums as a reason to support “Medicare-for-All” type proposals. As shown in the figure below, nearly 50% of people polled strongly favored proposals that allow people between 50 and 64 years of age to buy in to Medicare, or allow people to buy in to Medicaid, or create a plan like Medicare that is available to anyone. Getting insurance from a single government plan is strongly favored by only 34% of respondents.

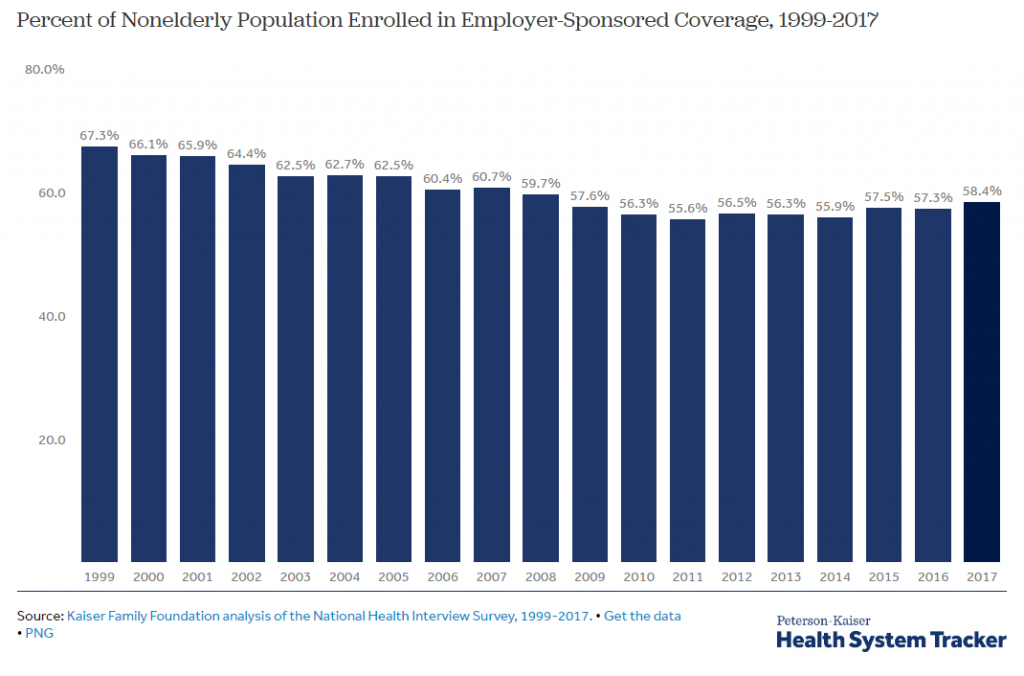

These “buy-in” proposals may be gaining in popularity as people lose access to employer-sponsored insurance. Here is the math: “if the coverage rate for employer-sponsored insurance was the same in 2017 as it was in 1999 (67.3%), almost 24 million (or 23.8 million) additional people would be covered through an employer plan in 2017.”

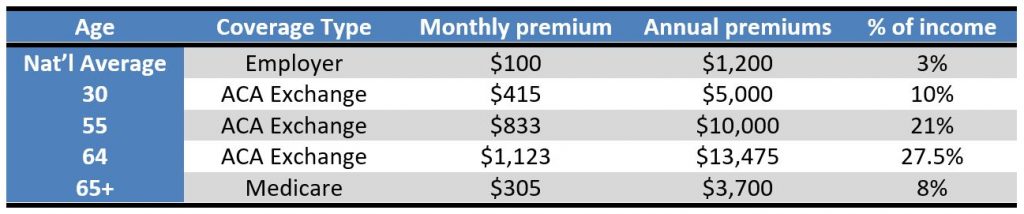

It’s easy to understand why people would focus on lower health care premiums; rising premiums are having a big impact on household incomes. As fewer people are receiving health insurance through their employer, they are also being exposed to higher costs for health care premiums. We pulled recent information on employer and worker contributions for health insurance, the average national premium for a person earning just over 400% of FPL ($49,000) to buy a health plan on the ACA Exchange at various ages, and Medicare premiums. We then created a rough comparison chart of what premiums an individual might have to pay for health insurance based on how they accessed coverage. Below is what we found:

Notably, the average annual premium for employer-sponsored coverage of an individual was about $6,900 last year. But employees usually paid just 18% of that amount. For people who may have been covered by their employer for years, and then have to buy insurance in the ACA Exchange, the loss of that employer-sponsored contribution to their health insurance coverage could be quite a shock.

It’s a catchy phrase and easy to hashtag in social media, but is the appeal of Medicare-for-All driven largely by the hope that a person’s premiums will be lower? Is Medicare-for-All the best or only way to achieve lower premiums? As with all policy issues, we should probably start with the key question, “what problem are we trying to solve” and then go from there, always checking to see that we are, in fact, addressing the problem we are trying to solve with a workable solution.