It’s all about the premiums, for a tiny but mighty political powerhouse

It’s all about the premiums, for a tiny but mighty political powerhouse

On October 17, 2017, Senators Lamar Alexander (R-TN) and Patty Murray (D-WA) announced a bipartisan deal to “stabilize individual market premiums and provide meaningful state flexibility.” The latest “repeal and replace” proposal from Alexander/Murray came just a week after U.S. Health and Human Services (HHS) Acting Secretary Eric Hargan and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Administrator Seema Verma announced cost-sharing reduction (CSR) payments would be “discontinued immediately based on a legal opinion from the Attorney General.” Lots and lots has already been written about the CSR policy change (I recommend Timothy Jost’s piece in Health Affairs for a brief summary of the major issues).

Professor Jost explains the CSRs succinctly:

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires insurers to reduce cost sharing for individuals who enroll in silver plans and have household incomes not exceeding 250 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). These provisions reduce the out-of-pocket limit for these enrollees—particularly for those with incomes below 200 percent of poverty—and sharply reduce deductibles, coinsurance, and copayments. The reductions cost insurers around $7 billion a year currently.

Based in part on what the Senators heard from state officials in early September (see this ) the Alexander/Murray deal would continue to fund the CSRs for two years, would allow people of any age to purchase catastrophic health plans and would allow states even broader latitude to waive provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in order to lower premiums – for example, by allowing health insurers to offer products that do not cover all of the essential health benefits.

If lower priced products can’t be offered in the portion of the market that is unsubsidized, it is difficult to foresee how a bill gets through Congress. A tiny but mighty political powerhouse is fighting hard for a fix that solves a very particular problem in the current ACA structure.

It’s all about the premiums

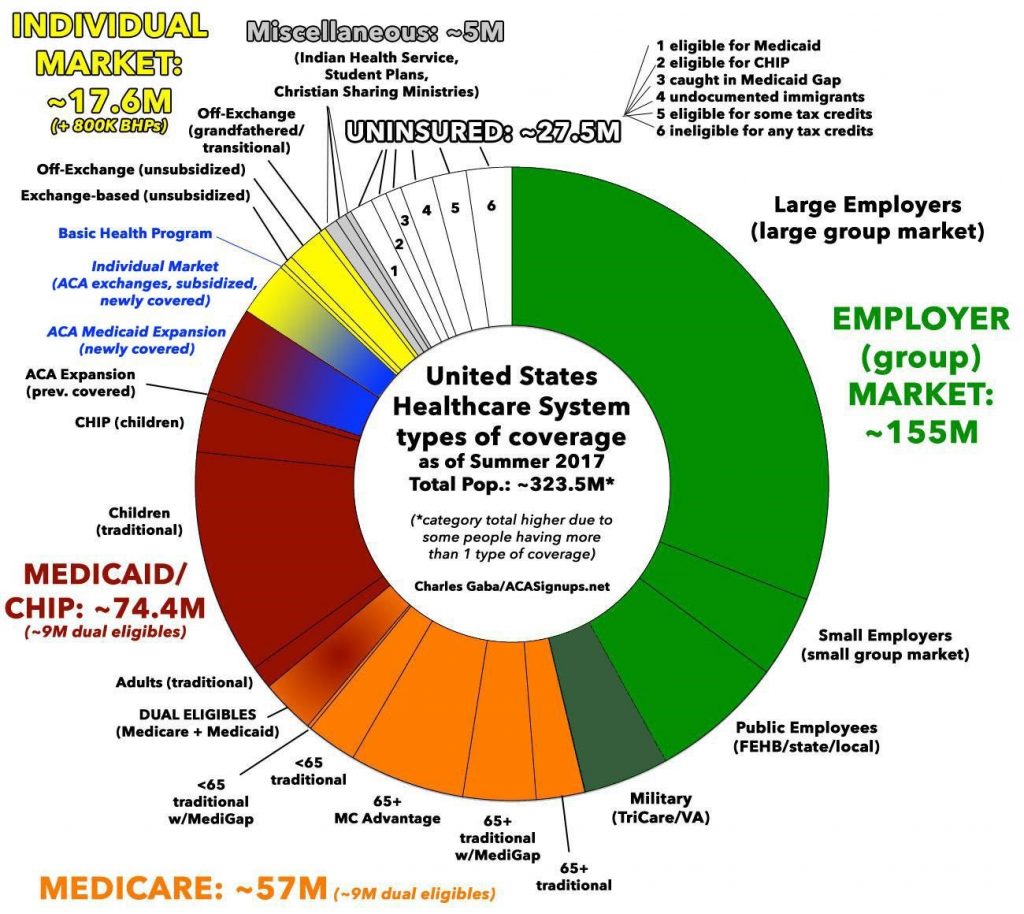

Keep in mind, about 17 million people receive their health insurance through the ACA health exchanges (see Charles Gaba chart – aka The Psychedelic Donut – below) – approximately 5% of the American public. Of those 17 million people, 1.6 million are in Exchange plans, but do not receive a subsidy. That is, health insurance companies are not obliged to reduce their premiums or cost-sharing requirements, most likely because they make more than 250 percent of FPL – about $30,000 for a single person, or $61,500 for a family of four.

Charles Gaba’s Psychedelic Donut Chart

Florida’s 6.6%

Let’s take the example of Florida. Just before the CSR announcement from the Trump Administration, one of the state’s largest insurers, Florida Blue, said it would be raising premiums, on average, 38 percent, for the 2018 plan year. A spokesperson explained:

“So who’s the one losing in this scenario? It’s the people who don’t get a subsidy to help out. Florida Blue has about 66,000 of their 1 million Obamacare customers who would have to cover the premium increases on their own. These are people with higher incomes, many who are maybe freelancers or self-employed.

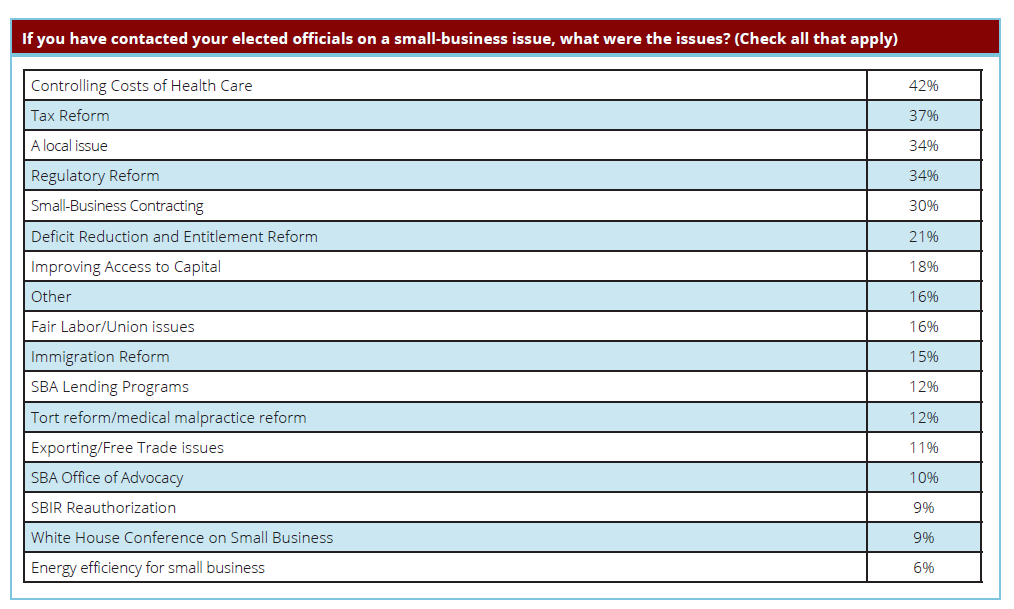

But who are those 66,000 people? In my estimation, that mighty 6.6%, and their counterparts across the U.S., are the ones who have effectively driven this policy change, and much of the “repeal and replace” demands over the past few years. Small business owners, especially tiny ones with fewer than five employees, are very focused on the issue of rising premiums and have been instrumental in communicating to their elected officials that their premiums are too high. The National Small Business Association (NSBA) 2016 Politics of Small Business Survey last year asked nearly 1,000 small business owners (47% of the respondents had five or fewer employees) what they contacted elected officials about.

What was the top issue? Controlling the costs of health care (see chart).

And amazingly, “97 percent of small-business owners say they vote regularly in national contests, compared to” only 58 percent turnout for the general election in 2012.

The Florida Blue spokesperson explained why this is such a hot-button issue for these politically-motivated, non-CSR-receiving, small business owners:

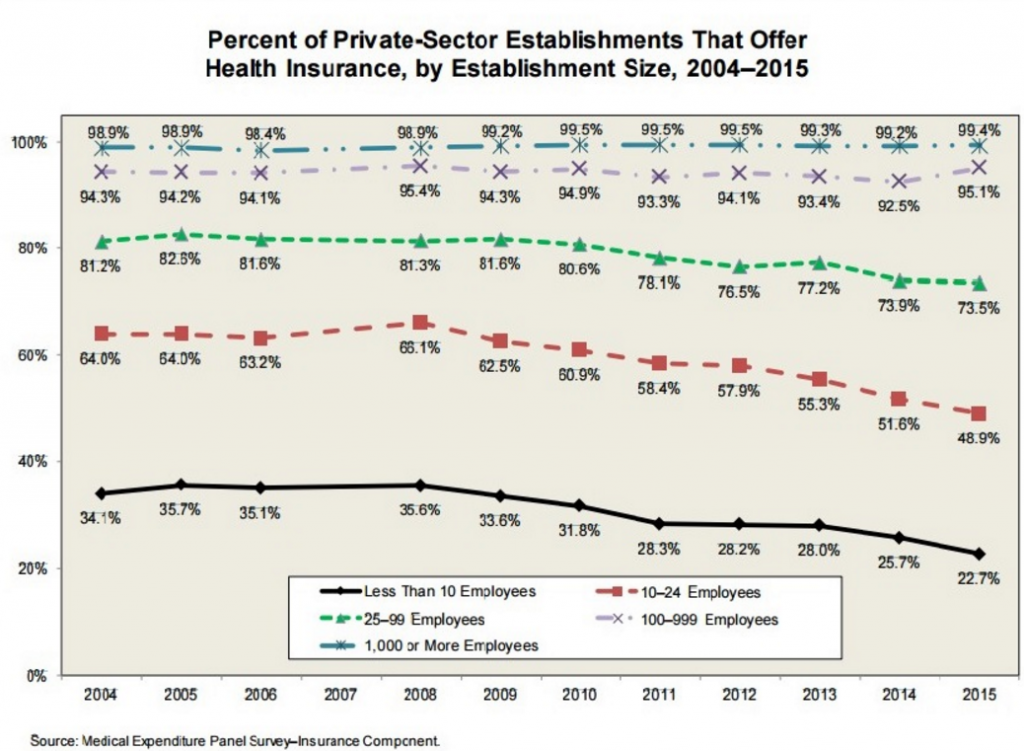

“The good news in all this: most people in Florida get private health insurance through their work. Those increases are going to be much more normal – about 8 percent on average for small companies.”

There is the whole issue in a nutshell. If you run a business or are self-employed and you make more than about $30,000 a year, you pay high premiums that jump 20, 30, 40 percent or more a year. In Florida, the average premium increase on the Exchange will be 45 percent in 2018, and the highest approved rate increase was 71 percent according to the Florida Office of Insurance Regulation. But if you buy the same insurance a slightly different way, either by becoming self-insured or becoming an employee of a bigger company, your premium increase will not be as great.

As Washington and the states continue to debate “repealing and replacing” the Affordable Care Act, keep an eye on what policy proposals mean for the politically-active small business owner. Fixes such as allowing anyone to buy catastrophic health plans (not just those under the age of 30) or allowing health insurers to sell products that offer fewer benefits will likely lower the premiums for people who buy health insurance on their own, whether tiny businesses or freelancers. Stopping payment of the CSRs won’t fix the problem small business voters are having with health care. If a proposal fixes this tiny but mighty political group’s problem with the ACA, the likelihood of passage improves immensely.