Pharmacist Substitution of Biosimilars: An Overview of State Laws

Cost savings through competition

Introducing generic versions of innovative medicines reduces prescription drug costs for consumers. According to the Generic Pharmaceutical Association (GPhA), increasing competition by introducing generic drugs led to $1.68 trillion in cost savings between 2005 and 2014. The GPhA also encourages competition for biologics, for example, by creating policies that improve access to “generic” versions, properly called biosimilars, stating: “These policies would provide American consumers with more choices, greater access to medicines, and billions of dollars in increased savings.”

The RAND Corporation reviewed studies of cost savings estimates from the introduction of biosimilars in the U.S. over a 10 year period and found savings estimates up to $108 billion and a range of price reduction from 10 to 50%.

State laws on pharmacist substitution of biologic products

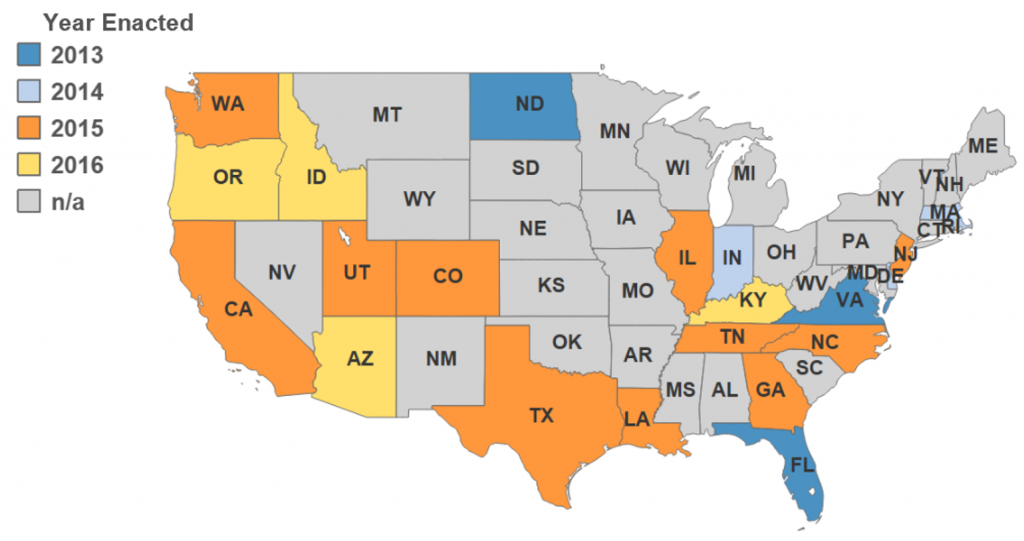

Because a biologic is fundamentally different from a chemically synthesized drug, state laws need to be updated in order to advance consumer access to biosimilar medicines. Since 2013, states have been attempting to clarify when and how a pharmacist can substitute a “biosimilar” for a biological product that has been prescribed by a health care provider. As of May 31, 2016, 21 states have passed laws allowing pharmacists to substitute an interchangeable biologic product for a prescribed biologic under certain circumstances. (See map)

Exact language varies by state, however, there are a number of similar provisions, including:

- Interchangeability—In order to be substituted by a pharmacist, the FDA must have approved the biosimilar as “interchangeable.”

- Provider override of substitution—The prescribing provider may prevent a substitution, usually by indicating “do not substitute”, “dispense as written”, or “brand medically necessary”.

- Provider notification requirements—The prescribing provider must be notified of a substitution, typically within five days of dispensing. States may also require the patient or patient’s representative to be notified of the substitution or, in some cases, consent to the substitution.

- Link to FDA-approved substitutions—Many state biosimilar laws require the Board of Pharmacy or some other state entity to maintain a link to the website listing of FDA-approved substitutions.

Why do state laws need to change?

Generally speaking, pharmacist substitution is permitted — or, in some states, required — if: (1) the drugs are therapeutically equivalent, (2) the substituted drug is less expensive, and (3) the prescriber has not precluded substitution, for example, by writing brand medically necessary or dispense as written (DAW). Many state statutes explicitly cite the Orange Book[1] as the basis for automatic substitution, however, the Orange Book does not address biologic products. As such, some observers have commented that, “under current law in most states, automatically substituting a biosimilar for the reference product may be interpreted as being beyond the pharmacist’s scope of practice.”[2]

States that have passed laws allowing pharmacist substitutions of biologics have addressed this uncertainty by making clear that pharmacists may consider a biological product for substitution if it has been approved as “interchangeable” by the FDA.

This approach is squarely in line with the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2010, the federal law which establishes an approval pathway for biosimilars. The BPCIA is clear that an interchangeable biosimilar “may be substituted for the reference product without the intervention” of the prescribing health care provider.[3] “Biosimilars: Implications for Health-System Pharmacists” published in the American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy in 2013, reiterated “Only interchangeable biosimilars are substitutable by a pharmacist without the intervention of the prescriber.”[4]

As of May 31, 2016, two products have gained approval by the FDA as a biosimilar, but not yet interchangeable. Zarxio, a biosimilar to Amgen Inc.’s Neupogen (filgrastim) was approved March 6, 2015, and Inflectra, a biosimilar to Janssen Biotech, Inc.’s Remicade (infliximab), was approved April 5, 2016.

References:

[1] The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) publishes a list of drugs classified as being therapeutically equivalent in the Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, otherwise known as the “Orange Book.”

[2] Li E, Hoffman JM. Implications of the FDA draft guidance on biosimilars for clinicians: what we know and don’t know. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013; 11(4): 368-372.

[3] PHSA §351(i)(3), 42 U.S.C. § 262(i)(3).

[4] Lucio SD, Stevenson JG and Hoffman JM. Biosimilars: Implications for health-system pharmacists. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2013; 70:2004-2017.